-

A11におけるMetal 2 - Imageblock

Imageblockは、Metal 2 Appにおいて、A11 GPUの高帯域幅タイルメモリにおけるカスタムのピクセル毎のデータ構造の定義や操作を可能にします。Imageblockがフラグメントとタイルステージのレンダリングパスの間でデータを受け渡す方法、準不同半透明などの高度なレンダリング手法をアンロックする方法について確認します。

リソース

- Tailor Your Apps for Apple GPUs and Tile-Based Deferred Rendering

- Forward Plus with Tile Shading

- Order Independent Transparency with Imageblocks

関連ビデオ

Tech Talks

-

このビデオを検索

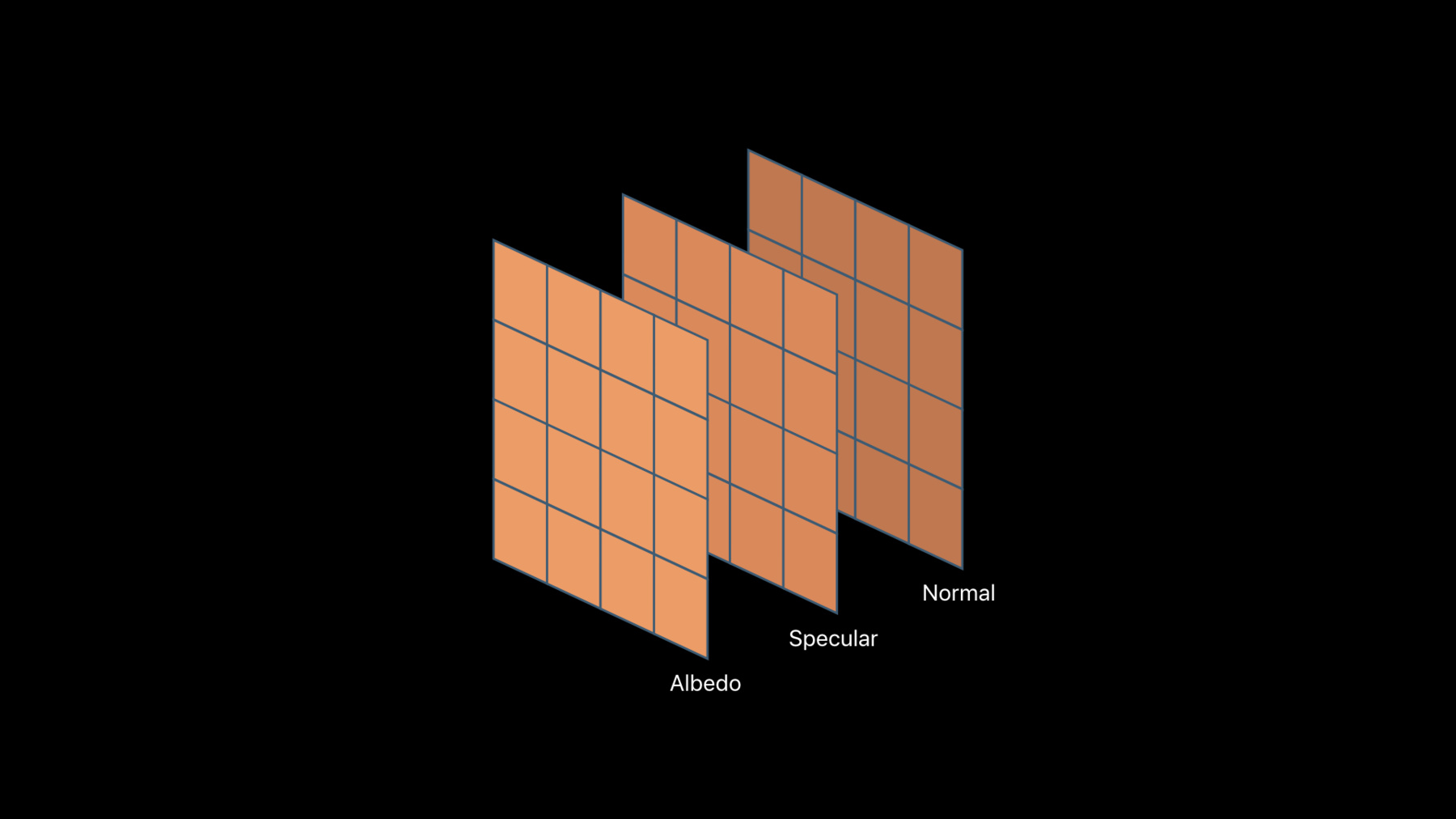

In this presentation we will focus on imageblocks, which allow you to describe image data in tile memory that the GPU can manipulate efficiently. Imageblocks provide optimized access to image data residing in tile memory. And with the A11 GPU, we're giving you direct control of it. You will be able to lay out pixels in the way that makes sense to your application, as well as move data explicitly to and from it. Imageblocks are deeply integrated with fragment processing and the new tile shading stage. They are also available to traditional compute. No matter which stage you're in, imageblocks are recommended for representing your images because they optimize access to grids of 2D data. Imageblocks are a key building block for several of the other features we'll discuss in this presentation series. Let's start by defining imageblocks more precisely. An Imageblock is a 2D data structure in tile memory. It has width, height, and a pixel depth. Fragment functions can only access a single pixel that corresponds to its location. Compute kernels, on the other hand, have access to the entire imageblock. Each pixel can be quite complex, consisting of multiple components, and each component can be addressed as its own image plane. This allows adjacent components to be efficiently stored to one or more textures in device memory as bulk operations. Imageblocks also provide bulk access to the GPU's format conversion hardware. Floating point pixels will be converted to the destination texture format when stored to device memory. Let's now take a closer look at one of the benefits of using imageblocks, accelerating image data movement out of tile memory. Prior to imageblocks, you probably moved portions of your textures into threadgroup memory before operating on them, one pixel at a time. But the GPU didn't understand that you were operating on image data, so you also had to store those pixels back out to device memory textures, one pixel at a time. With imageblocks, you can instead store the image data using a single operation, which is much more efficient. Now let's turn to how you describe imageblock properties to Metal. In a compute pass, you describe the imageblock's width and height using the API shown here. The dimensions can be different for each dispatch. The imageblock's pixel depth is described in the shading language as a structure. The entire imageblock is made available as an argument whose type is templated by that struct. Let's take a closer look at the shading language syntax. In this example, we are describing a pixel consisting of three elements, each with a varying number of components. The imageblock is made available to the kernel as an argument. Kernels access any location within the imageblock by reference using the data method, which takes the location as its argument and returns a pointer to a new address space called threadgroup_imageblock. With a reference to a particular location, we can read and write to elements at that location. I mentioned earlier that imageblocks are laid out in planes that can be stored efficiently to device memory textures. In the shading language, we call adjacent planes that can be stored together a slice. Let's take a look at an example kernel. In this example, we've loaded a source texture into an imageblock, performed some image processing on that block, and are ready to store the color elements out to a destination texture. We only need one thread of our threadgroup to perform the write, so we must first barrier to ensure all threads have finished processing the imageblock. Notice that Metal adds a new memory target for the barrier, declaring that we only need to wait for writes on the imageblock to complete. We then acquire our desired slice from the imageblock using the slice method. The slice method takes a reference to any pixel element that's part of the slice. Finally, we write the slice to the destination texture.

Each imageblock probably represents only a region of your texture, so we specify the texture offset at which to write the imageblock. Let's now turn to how imageblocks in fragment functions are specified. Unlike imageblocks in compute passes, imageblock dimensions in a render pass are constant for the entire pass and set using the properties shown here. Imageblock pixel depth can be declared in the shading language as a struct, just as I've already shown for kernels. Fragment functions, however, also support declaring the pixel depth using render pass attachments. Let's take a look at the syntax. In this example, we've declared the pixel structure explicitly in the shading language. Since fragment functions only have access to their implied location within the imageblock, the argument type is the struct itself, but tagged with the imageblock_data attribute. We also need to tag the return value with the same attribute. Doing so allows Metal to generate the correct access instructions. Now let's see what this same example looks like when we declare the pixel structure using traditional render pass attachments. This form is identical to the syntax you already know. In fact, you've always used imageblocks in render passes because tile memory has always been a key aspect of A-series GPUs. What's new is that Metal 2 now makes tile memory generally accessible. This form abstracts the underlying imageblock storage format, which is derived from the textures attached to the render pass. Regardless of texture storage type, the data is presented as floating point or integer in the fragment function.

Another difference between A11 and earlier architectures is where those implicit imageblock format conversions occur. On A7 through A10 GPUs, the storage formats were expanded to floating point in tile memory. This is why Metal documents two sizes for every pixel format: one when stored in device memory and one when stored in tile memory as render pass attachments. On A11, format conversion occurs on each load and store from tile memory to temporary registers in the shader core. Doing so allows you to squeeze even more use out of tile memory.

You now have a choice in how to declare your pixel structure, so let's review best practices that can help you decide. Implicit imageblocks are great when your fragment function must support multiple render pass attachment layouts because they abstract the underlying storage formats. Implicit imageblocks are also compatible with load and store actions because the structure is known by the API. Explicit imageblocks on the other hand allow you to express more complex pixel structure. Explicit imageblocks also don't require main memory backing, so they're a great fit for temporary data produced and consumed entirely within the scope of a render pass. Now let's take a closer look at what we mean by complex pixel structure. In this example, we're going to store multiple translucent colors and their depths per pixel so that we can later sort and composite for more accurate transparency effects. We start with a single fragment declaration, declare an array of them, and then nest it in a top-level struct that we can pass to and from our shader. Expressing this structure using render pass attachments would be awkward and would obscure the author's intent. Of course, you don't have to choose between implicit and explicit forms because Metal allows you to pick the right tool for the job. Mixing also allows you to incrementally adopt imageblocks into your code base and easily integrate new features into existing shaders that benefit from the explicit form. Using both forms together is easy, just provide two imageblock arguments. Let's take a look at an example. As you can see, we can supply two imageblocks as both inputs and outputs. The color and imageblock_data attributes make it clear to Metal which slices derive from render pass attachments and which do not. Up to two imageblocks per input and output can be declared for each function.

Explicit imageblocks allow you to control pixel layout exactly using packed types. The Metal shading language already provides packed floating point vector types, which have traditionally described vertex and constant data layouts. But now we need packed types that match what could have previously been described using implicit imageblocks and texture pixel formats. Metal 2 adds such types to the shading language. These formats are converted to and from floating point using the load/store hardware we discussed earlier. What's more is that these new packed formats can be used to describe vertex and constant data layouts, too. Let's take a look at how you declare these new types in the shading language. In this example we see a few of the new packed types used to describe both imageblocks and vertex data. These types require that you declare both the storage format and unpack format used within the shader core. Now let's glance at all the new packed data types that have been added. As you can see, the Metal shading language adds one, two, and four component normalized types, each supporting eight or 16-bit components. We've also added both signed and unsigned variants as well as support for more specialized 32-bit formats such as 10a2, mini floats, shared exponent, and sRGB. Finally, the GPU debugger in Xcode directly supports the visualization and inspection of imageblocks. Each slice can be inspected as if it were a texture. Here we see on the top an example G-Buffer layout from our sample code. And on the bottom we have the same imageblock show in Xcode's GPU Debugger. The tile section of the bound resources view shows the imageblock slices as a set of textures. From here you can inspect each of the slices just like any other texture. In this presentation, we saw how imageblocks enable you to efficiently move multiple pixels from tile memory to device memory and control the layout of image data in tile memory precisely to improve storage density. We also saw how we could also leverage the A11 GPU's new pack/unpack hardware in both imageblocks and other address spaces. For more information about Metal 2 and links to the sample code, please visit the Developer website at developer.apple.com/metal. Thank you for watching!

-